Dead Castles in the Sea

Dead Castles in the Sea

By Patrick Saldaña

I moved to Florida in 2018 to study Caribbean coral reefs in Panama. Trained primarily as an experimental field ecologist, I spent almost five months in the region doing field experiments, surveys and deployments during my first field season. The compositional structure of these “dead castles” I work in are common throughout the Caribbean Sea, and although they have been heavily impacted by local and global anthropogenic impacts, I imagine they represent what the average person would envision a coral reef to look like: shallow, accessible by snorkel and colorful with a lot of light.

Deep sea diversity

Most tropical reef-forming corals maintain mutualistic relationships with zooxanthellae algae. These algae inhabit coral polyps and produce oxygen through photosynthesis (hence the light requirement for coral growth), supply corals with essential sugar and other organic compounds, and give corals the bright colors they are known for. In fact, a “bleached” coral exhibits a bright white coloration precisely because it has expelled its photosynthetic zooxanthellae. Tropical reefs are some of the most biodiverse habitats on Earth and contribute several ecosystem services that benefit coastal communities. However, tropical zooxanthellae-hosting corals are not the only reef-building corals in the ocean.

A tropical coral reef (~ 4 m depth) in Caribbean Panama from one of my field sites.

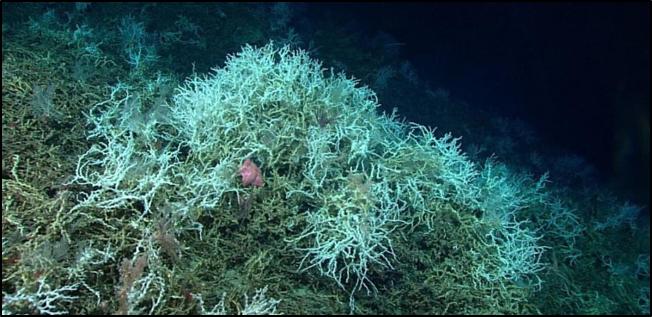

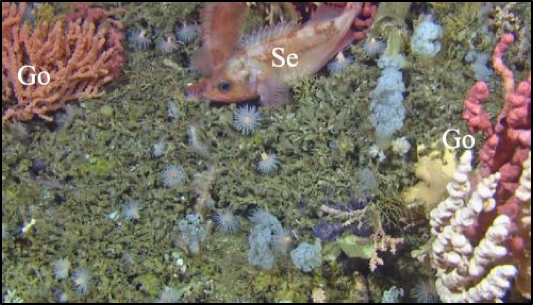

Scattered throughout the world and deep in the sea, at depths ranging from a few hundred to over six thousand feet, there are coral reefs inaccessible to most divers. The water is cold down there, sometimes even below freezing temperatures. Because of the extreme depth and environmental conditions in which these corals live, we know much less about them than their more popular tropical cousins. Known as cold-water corals (CWC), these animals do not host photosynthetic zooxanthellae and instead derive their food entirely from filtering small particles swept towards them by ocean currents. This strategy allows them to inhabit such deep depths devoid of light. However, just like tropical corals, CWCs are habitat-forming species and provide structural havens for biodiversity in an otherwise dark, desolate and structureless space.

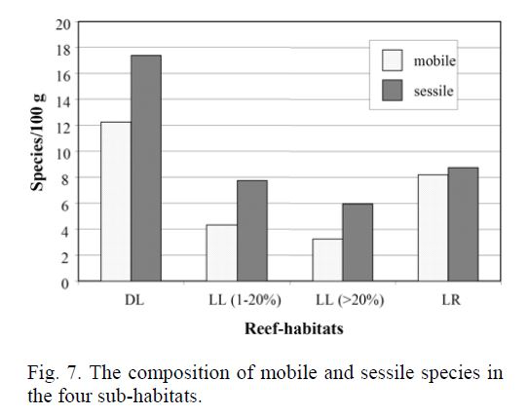

Although I have known about CWCs for a while, I had never spent much time reading about them until recently, when after being grounded from fieldwork (thanks Covid) I switched gears and began working on a meta-analysis/review paper. I was looking for papers that had quantified the relative proportion of dead and live habitat provided by habitat-forming organisms in marine systems, and CWCs were one of the few habitats where that had been consistently measured. It may be a bit unsurprising that reefs in the deep sea would harbor such incredible biodiversity, considering the otherwise desolate nature of that ecosystem. What may be surprising, is that although these structures were formed by live corals, the reefs providing such habitat are mostly dead. Not only are they mostly dead, but many studies have suggested that dead CWC habitats host higher biodiversity than their live counterparts.

I should note that this coral substrate isn’t just recently dead. Some of these coral mounds have been aged to 40,000 years old. The live corals growing on top of them, extending the reef, have been aged to 4,000 years old. Yep, that’s the oldest recorded age of any animal in the sea. Often rising to several meters above the seafloor, some of these giant dead structures (sometimes referred to as bioherms) have been around longer than the human species and are still being used as a home by diverse communities of fishes, crabs, worms and other invertebrates.

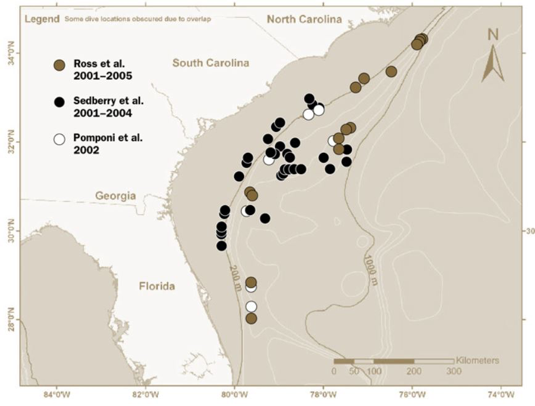

This means that some of the most biodiverse areas on the ocean floor throughout the world are being sustained largely by the dead remnants of extremely slow-growing species (many CWCs have growth rates of less than 0.5 cm/yr). I think that’s pretty incredible. And although most research on these systems has been on reefs in the northeast Atlantic, new regions with these deep-sea coral reefs are continuously being discovered. In fact, only in the last twenty years, a large stretch of CWCs was found off the southeast United States from North Carolina down to East Florida. These relic castles of the sea exist relatively close to us here in Gainesville, and yet we are only just discovering them.

Check out blog posts from other 2020-2021 Fellows.

References