2024-2025 BLOG POST

2024-2025 BLOG POST

Viviana Rojas Bonzi: Measuring Biodiversity in Natural Systems Truck and a Jaguar

Nicholas Gardner: Learning from Communities in the Peruvian Amazon

Rick Stanley: Palmchats of the Caribbean: Sun, Wind, and the Importance of Adaptability in Fieldwork

Annika Smith: Lessons from Flowers: How conflict can spur growth (and grow spurs!)

Palash Sethi: The Invisible Architects: BioLLMs and the Microbial Blueprint of Life

Viviana Rojas Bonzi: Exploring the Chaco: From Biodiversity to Battlefields

Hernan Alvarez: From Childhood Adventures to Scientific Curiosity to Understanding People: My Journey into the Human Side of Biodiversity Conservation

Rick Stanley: Ecosystem Recovery in the Dominican Republic

Liz Hurtado: A Birding Journey Across Northern Argentina

Viviana Rojas Bonzi

Fieldwork in the Heart of South America: a Broken Truck and a Jaguar

Read this story listening to “Sonidos del Chaco Seco” by Juan Pablo Culasso on Spotify.

During my field work in 2023, my team and I had what someone would call “a full Chaco experience” all in one day -because that is the Chaco- full intensity and beauty at all the same time, sometimes faster than you can process. This is the story of that day.

Often overlooked or simply forgotten, the heart of South America is home to one of the most remarkable yet understudied ecoregions. The Chaco Forest is a sprawling dry forest that is twice the size of France and extends into Paraguay, Bolivia, Argentina. A dry forest, you might wonder—what exactly does that mean?

Imagine a place where the sun reigns supreme, pouring its light over a vast plain that seems to stretch into infinity. Here, the land breathes dry heat, and the horizon illuminates under the weight of cloudless skies. This is the dry forest—a place where life has learned to thrive against the odds, sculpted by long periods of pressing heat and little rain, where biodiversity tells a story of resilience whispering through thorny trees and strong shrubs that stretch their roots deep into the earth, seeking hidden reservoirs of water. The soil is hard, cracked—broken, some might say—where its earthy color contrasts with the washed-out green of quebracho and algarrobo trees. The Chaco is not an easy landscape; for many, its beauty does not reveal itself immediately. However, for those willing to see—and feel—in this place, every plant and every animal tells a story of struggle, adaptation, and balance.

Cerro Leon, Paraguayan Chaco. Photo: Cara Pratt, WWF-Paraguay

Paradoxically, venturing into the hot Chaco forest compels us to use gear that resembles armor more than anything else. Heavy and thick shirts and pants, socks over pants as a desperate effort to avoid the bite of a lurking tick, and “snake chaps” become a must, because it’s not only the snakes that bite, but the thorns also latch onto our clothes like a thief’s grasping hand. Sometimes -I think- our field gear is far from charismatic, it is rather a sharp contrast to the charming image of a field biologist that one might envision, with breathable shirts and shorts.

Our day started like any other, 4:30am, waking, breakfast, prepare snacks, prepare the equipment, start the truck, load the essentials: water, ice (if we are lucky to still have some), first aid equipment for the team and truck, and emergency phone. We were ready. As we hear the endemic “black-legged seriema” we witnessed the sun rise as we drove to our field site, the windows rolled down to savor the only moments with a pleasant breeze, before the pressing heat would redden our cheeks. Bouncing in the truck with every pothole that shapes the dirt road, a conspiratorial silence is felt as we exchange glances among those who have traveled roads like these too many times to count, signaling that this route could bring complications. “We can’t return too late; we need to outpace the sunset”- one team member says.

We reach our field site and, as we venture into the forest, the air feels heavy, and the scent of the “palo santo” tree fills every breath. Silence dominates the landscape, broken only by the sound of dry branches and the song of a stripe-backed antbird announcing our intrusive presence in the forest. The quebracho trees stand firm, watching as you carve our way through with a machete, which rebounds against the unbreakable trunks, making a sound like tolling bells. The old guayacan tree seems to laugh as it sees us trying to advance. The Samu’u trees offer their thorny bark for support, and as one tries to catch a breath, we can’t help but to look up and admire their splendor—their vast, bulging trunks that give them the name “palo borracho,” or “drunken stick,” perhaps due to their belly-like shape. The cacti, with trunks so thick they resemble trees, have defied time and climate, some even displaying a modest white flower that stands out among the washed-out green, almost yellow landscape. Between the stillness air and a forest that pulses life, we forge ahead.

We try to advance in a straight line, but it’s an impossible mission; with trees, shrubs and cacti acting like barricades, they force us to take extra steps to reach our desired sites. With every few steps, we look back to sketch the landscape and our path into our memory. Yet, as if by magic, as if the forest wants to swallow us, everything appears untouched when we look back, despite the trail we’ve blazed. However, we’ve learned to mark our way more astutely, adding a touch of fluorescent pink ribbons to the scenery. Finally, we reach our site into the forest, drop our heavy backpacks and, and as we lift our heads to drink a much desired and deserved zip of water, our eyes meet the magnificent canopy, dancing like it is in slow motion. We take a few moments to decide the best place to install our equipment, which is includes remotely triggered camera traps to capture wildlife pictures and acoustic recorders to gather information on human disturbance. We look for signs of animal paths and a trunk that could serve us to mount the cameras and monitor, and once there is consensus, we take a heavy breath and start. As the days go by, we become more efficient, everyone knows exactly what to do: clean shrubs, write down coordinates, save GPS track (because we need to come back!), mount the cameras, trigger cameras to test, check date and time, secure camera, gather our stuff, look around to find our fluorescent pink ribbons, and walk back to the car as we admire how we manage to forge into this thick forest. Sometimes it would take hours just to do a couple of meters into the forest. We repeat this endeavor 2 or 3 times a day, we end up exhausted. Field-work exhausted.

On this day, we agreed to finish rather early. Overwhelmed by the heat, but with a feeling of satisfaction for having completed our task at one of the most challenging sites, we began our return. We are only a little over 150 km from our resting site, but with the cracked roads that slowed us down, we were looking at 3 hours return drive. As we rolled down the windows, the warm breeze of this 40 C-day that was coming to an end brushed against our faces. We drove at a slow pace – the road won’t allow us to go any faster- enjoying our return, turning our heads every now and then admiring the flocks of blue-fronted parrots returning to rest, as well. Feeling more relaxed, and with ice to spare, we could finally enjoy our “terere”.

The road began to worsen, and the truck started showing its first signs that we needed to slow down even more. Drinking tereré became more challenging with each bump. We exchanged glances at every sound of a loose gear we heard while watching the sun set, painting the silhouette of the cacti. The dim light of the impending sunset made our journey difficult, and suddenly, as if by surprise, our heads hit the roof of the truck—a loud clatter of loose ends alerted us that we had fallen into a pothole. The truck came to a halt. Silence flooded the cabin as a look of concern appeared on each of our faces. It’s getting dark, we need to get out of here. After a few grueling minutes, we managed to get out of the pothole. We assessed the situation and realized that something was loose at the bottom of the truck. We nervously improvised a temporary solution with the tape and ropes we had, enough at least to get to our resting site and look for a mechanic the next day. Finally, we managed to continue.

The road seemed endless. For some reason, the truck’s headlights were no longer enough, so, like good improvisers, we sat on the windows and aimed our headlamps outside. The contribution was minimal, but it felt necessary. The sunset became more evident, as the “Chaco chachalaca” announced the imminent reign of the moon. One of us, the one with the sharpest vision, began to furrow his brow and hesitantly mentioned: -“There are fresh cat tracks here. Stop, let’s take a look!”, he urged. Uncomfortable with the request, knowing we might not be able to start the truck again, curiosity and the possibility of experiencing a first encounter overwhelmed us. We stopped the truck. Silence returned, but this time it was heavier. The tracks were fresh. The tracks were of a cat. The tracks were of a jaguar. Excitement took over, only to be overwhelmed by a bit of uncertainty. Did we pass it? Did it see us and hide? Is it watching us?

We took a few minutes to explore our surroundings, one of us already with a finger on the camera shutter. Sighs of disappointment. “Let’s go, before it gets too dark,” we decided. We got back in, and after a few attempts, we started the truck and continued. It didn’t take many seconds, and even fewer meters, before a sudden stop surprised us. A finger pointed decisively at the path, “There it is! Do you see it?!”

The majestic jaguar was sharing our path. In silent agreement, the truck stopped. We all watched in disbelief at our first encounter with the king of this forest. Its heavy gait, responsible for the beautiful and distinct tracks, became a delight. He stopped, observed us with the deepest gaze we had ever experienced, only to disappear into the vegetation, leaving the landscape empty as if nothing had happened. An experience that was only a few seconds seemed like several minutes.

As we arrived under the reign of the moon, the night was marked by the endless repetition of the details that led us to this moment. We thought that the Chaco planned this, we were convinced that it delayed us for a few hours only to allow us to coincide with this moment. And so, thanks to our mishaps, we all received the grand prize, the most awaited encounter.

Some skeptics might say, “If there’s no photo, it didn’t happen.” Luckily for us, there is a picture. It did happen.

Nicholas Gardner

Learning from Communities in the Peruvian Amazon

Recently, someone asked me about my interest in working with communities. Two minutes into my passionate ramble about understory antbird species assemblages (I regret nothing, they’re amazing), I realized they meant communities of the human variety. You know, people. Their question referred to the fieldwork for my latest thesis chapter, which has been an unexpected but enlightening dive into the social dimensions of conservation.

Working directly with local people is, to my shame, almost completely new to me. I’ve been on plenty of projects with local biologists, experts and guides, but rarely more than that. The deeper I delve into it, the more I’m beginning to think that understanding human communities is far more complex than untangling the intricate interactions of an Amazonian forest. Of course, it’s also just as important.

From Birds to People

My fieldwork takes me to the Peruvian Amazon, a few boat hours south of Iquitos, Loreto’s chaotic capital. It’s always a relief to leave the motorbike taxi horns behind and glide along the vine-draped meanders of the Tahuayo and Yanayacu rivers, where rush hour consists of the cacophonous calls of blue-and-yellow Macaws and the occasional passing fishing boat. Most of my research revolves around acoustic monitoring, surveying bird communities during the seasonal flooding months between February and May. While this work is providing fascinating ecological and phenological insights, I wanted to tackle something with a more direct conservation impact.

Enter the Wattled Curassow (Crax globulosa) —a charismatic and endangered bird species that inhabits the seasonally flooded “várzea” forests around Muyuna Lodge, an ecotourism hub. I’ll admit, my initial reasoning for studying the curassow was something like “Wow, look at that thing!” Really though, look at it. It’s a turkey sized bird with a quiff and a red blob on its face that spends most of its time in the canopy of flooded forests. It’s objectively cool. By all accounts it’s also objectively, tragically delicious. Thankfully, nearby villagers no longer hunt the curassows, relying on other income sources. As weird, wonderful and rare as this bird is, the project quickly tapped into something much bigger, pushing me to truly engage with local communities and learn about the intricate social dynamics tied to conservation in the area.

Navigating Lodge-Community Dynamics

The lodge recently established a partner non-profit foundation aimed at supporting scientific research and fostering closer ties between conservation and local communities. This is where things get complicated. The nearby villages of San Juan and Ayacucho have long been connected to the lodge through employment and education initiatives. However, during my initial meetings with community members, it became clear that there’s a lingering tension. Some villagers perceive the ecolodge’s efforts as uneven, favoring its own interests over those of the broader community. The foundation employs locals and funds education programs, but these concerns clearly highlight a deeper layer of mistrust. Given the long and, at times, horrific history of outsiders coming in and generating income in the area (think rubber booms), this ingrained mistrust of ecotourism and fear of exploitation is more than warranted. I walked into the first community meeting thinking that our goal was to sell the scientific merit of camera traps and acoustic monitors, and present the training and educational opportunities that the project offers. Wrong, of course. Within minutes, the true goal became clear: reassurance.

The villagers I spoke with were polite but firm in their objections. They questioned how my work would benefit their communities and whether it would perpetuate existing inequalities. Luckily, I was not alone. Santiago, the head of the foundation, and Luis, a respected local leader, played crucial roles in bridging cultural gaps and interpreting our proposals in terms that resonated with community members. It took several more meetings, but we ended up with a plan and a list of participants.

Lessons Learned (and Still Learning)

This experience has been humbling, to say the least. As a biologist, I’m used to thinking about conservation in terms of species and ecosystems. Sitting in a community meeting, however, and facing hard questions about equity and trust is an entirely different challenge. It has reshaped my understanding of the role of science in conservation and highlighted the critical importance of transparency and collaboration.

To address the concerns raised, I’ve started working closely with the Muyuna Foundation and several community leaders to better communicate the potential benefits of the project. We’re exploring ways to involve community members in fieldwork, from data collection to educational workshops about the Wattled Curassow’s ecological role and conservation significance. These steps are small, but they’re a start toward building trust and ensuring that conservation efforts align with local priorities.

Looking Ahead

This chapter of my research really represents a pilot study of sorts, but I’m optimistic about where it’s heading. I’ve come to see the challenges of community engagement as opportunities for growth—both personally and professionally. Working with people may never feel as straightforward as analyzing terabytes of passive acoustic data, but it’s teaching me important lessons about the importance of connectedness in conservation, about humility. Oh, and about advanced boating manoeuvres.

I’ll be back in Peru in February. I’m excited to see how this project evolves and to share its progress. And camera trap videos, because who doesn’t love those?

Rick Stanley

Palmchats of the Caribbean: Sun, wind, and the importance of adaptability in fieldwork

The first rule of field work seems to be this: the one thing you can always count on is that hardly anything will go according to plan. Every new field season brings a fresh reminder of this principle. Sometimes, travel delays pose the biggest obstacle. In the past, I have struggled getting to and from field sites: on one trip, civil unrest blocked off access to the airport; on another, flooding turned the only access road to a national park into a raging torrent, stranding me inside. Other times, the species being researched poses the challenge. While conducting research on montane birds in Indonesia, for instance, I found that the extreme rarity of certain species made them nearly impossible to gather data on.

This time, while conducting field work for my PhD in the Dominican Republic, it would turn out to be the weather that would throw a wrench into my fieldwork plans.

As an ecologist focusing on birds, I love exploring remote locations, but the field site in the Dominican Republic that I ultimately chose for my PhD dissertation is relatively tame. Having experienced the ups and downs of fieldwork in remote localities, I decided that an easily accessible, beautiful coastal field site not far from a major airport and beach resort would make a safe and reliable location for setting up a long-term project. What could possibly go wrong? Soon, I had packed my binoculars and set out for the Caribbean, looking forward to spending my days surrounded by turquoise seas, swaying palm trees, and dense tropical dry forests growing on porous white limestone.

I chose my field site in part because it was bustling with the species that I planned to study. The Palmchat (Dulus dominicus) is a unique endemic, found only on the island of Hispaniola. About the size of a robin, with brown wings and back and a streaked breast, the Palmchat’s humble coloration belies its unique and fascinating lifestyle. In fact, it is one of the only birds in the world to live in communal nests: something like the avian equivalent of

an apartment complex. These enormous nests are constructed cooperatively together with an extended family of Palmchats: as many as forty Palmchats can live together in a single, multi-story nest, making this species an ideal subject for research on complex social cooperation. These nest complexes even provide an important resource for a diversity of other species, such as the critically endangered Ridgway’s Hawk, making the Palmchat a true ecosystem engineer.

The plan was simple enough. I would capture enough Palmchats to study the species in detail, fitting them with unique color-bands and following their behavior as they went about their daily lives—only now, I would recognize each wild bird by an individual color code. This idea was complicated by a few potential pitfalls. Firstly, the Palmchat is a canopy-dwelling species, so it spends most of its time at the tops of trees that are anywhere from 10 to 20 meters high—well outside of the reach of the mist nets commonly used in ornithological research. Secondly, there was also the risk that any birds I did band would fly into the forest and never be seen again. Ultimately, though, I decided these challenges would be manageable with a little persistence. . . and with that, I began my fieldwork on Palmchats in Punta Cana.

In the field with the Palmchat dream team: UF PhD students Rick Stanley, Marlyn Zuluaga, Liz Hurtado, Wenyi Zhou (Punta Cana, Dominican Republic)

With the help of an amazing field team, things were going remarkably smoothly. I solved the canopy height problem by constructing 20-foot tall, custom-built mist-netting poles, successfully figuring out how to capture this high-flying species. Using a spotting scope with high magnification, I found that I could read the band colors off of even distant Palmchats, allowing me to gain interesting new insights into the behavior and biology of this little-studied species.

It was all going a little too well. Not long after my first field season ended, a hurricane came rolling in. It turns out that the kryptonite of a Palmchat researcher is wind. By the time that it reached my field site, the hurricane’s windspeed had dropped slightly to tropical-storm levels, but the storm still hit my bird population with great ferocity, tearing nests down from trees, and scattering the normally sociable and densely clustered birds far and wide. The ten large nests that I had chosen as my primary study population were all damaged, and the palm fronds supporting them were broken off. It looked as though all might be lost.

Nature, however, can be extremely resilient. Hurricanes are an integral part of life in the Caribbean, and the local ecosystems have been adapting to them for millennia. While the effects of the storm appeared disastrous in the short term, losing their homes to a hurricane was nothing that the Palmchats had not seen before. They soon started to rebuild. I can think of few species that are more industrious builders: with the teamwork of many different cooperating birds, the Palmchats had a completely new multi-story nest complex constructed in short order. However, most of the Palmchats had chosen not to return to the same nesting sites where I had expected to conduct my study, instead opting to spread out and colonize new localities.

Nothing was going remotely according to my plans, but due to the resilience of the Palmchats, I realized that it would still be possible for me to get data. I would just have to rethink my field site and follow the Palmchats’ lead. As a result of the storm, I relocated my primary field site to a new location a couple miles away from where I had initially planned to work.

It may be tempting to view unplanned events like this storm as setbacks or even disasters. However, in my case, the new field site proved superior to the original spot. The trees were less tall, views of the birds were less obstructed, and the clearer surroundings made it easier to situate nets and field equipment. You could even say that I owe the success of my entire project to serendipity, because the storm that sent me packing and threatened to ruin my project ultimately nudged my field plans in a more productive direction. Like the Palmchats, I learned that the best course of action was to adapt, and most importantly, to start rebuilding as soon as the storm had passed.

Annika Smith

Lessons from Flowers: How conflict can spur growth (and grow spurs!)

Let’s talk about the lessons we can learn from flowers in times of tension and conflict. These are certainly strange and challenging moments in history, with large-scale disharmonies and cataclysms taking various forms across the levels of society and our planet. “Flowers?”, you might inquire skeptically, “when wildfires are raging, species are going extinct, bombs are falling, human rights are threatened, and governments are crumbling?” Gazing at flowers, contemplating their diversity, how they came to be, enjoying their beauty— it is understandable if such activities might seem frivolous in such dire circumstances. How can any of us justify meditating on and meandering with flowers for more than a moment? When instead we could be working; taking care of our families, bodies, homes, pets; or spending our time and energy fighting to make the world a better place? What could flowers really have to teach us?

Flowers are dazzlingly diverse in form. We’ll focus on the processes of development that underlie the formation of the diverse and distinct shapes of flowers. There are countless ways that flowers and pollinators are linked in form and function, and similarly innumerable ways that simple tweaks in developmental process and underlying structure can lead to vast shifts in the final form of a flower. Certain clades of plants all have flowers that look more or less the same, while the diverse flowers of other clades reveal an inherent ease in their ability to change to fit the preferences of certain pollinators, or to keep out other, unwanted floral visitors. It can be hard to remember that plant families that are now wildly diverse once started with a single common ancestor, far back in time. But all of these different floral shapes and colors had to come into being somehow. Through the process of natural selection and hinging on a plant’s inherent potential for evolvability (involving things like underlying genetic diversity and developmental patterns)— flowers have shifted into extraordinarily different shapes and forms.

In graduate school, I was lured in by the floral diversity of the nasturtium family, Tropaeolaceae, comprised of a single genus, Tropaeolum. The nasturtium family is comprised of about 100 species, ranging from Mexico to Patagonia, heavily distributed along the Andes. This geographic distribution, along with their characteristic nectar spurs, signals a keen relationship with hummingbirds. And indeed, the highest species diversity of Tropaeolum overlaps with the area of the highest species diversity of hummingbirds. But they are not all hummingbird pollinated, as we shall see. Here we will focus on just two species, which can be found flowering at the same time, sometimes even in the same place as each other.

The following photos are ones I took during fieldwork in 2018 and 2019 in the central region of Chile. Over 25 species of the genus Tropaeolum are found throughout Chile — these two species, T. tricolor and T. azureum — have flowers with strikingly different shapes and colors. These are not flowers one could expect to admire all year— both species are spring ephemerals, fading quickly in the bright sunshine of the Mediterranean climate of central Chile. Both species rise out of the ground as slender, delicate vines in the early spring, fueled by starches from rounded tubers hidden under silty, rocky soil. They swiftly drape their surroundings, stems spiraling around the surrounding vegetation and the petioles of their hand-like, palmate leaves clasping around any support they can find for their yearning forms. One flower bud emerges from each node, the place the leaf petiole meets the stem of the plant.

Despite the vast difference in the appearance of their flowers, the two plants pictured here are essentially siblings in terms of their evolutionary relationships (Anderson & Anderson, 2001; Hershekovitz, 2006). Additionally, they both grow and flower at around the same time, have similar vegetative growth, and they can grow in similar habitats, with parts of their ranges even overlapping. Where they diverge is predicated o the distinct shapes and colors of their flowers— they are able to maintain distinct ecological functions and relationships.

In my research, I’ve spent a great deal of time examining the anatomy of these flowers, especially through CT scans that capture their development in detail. I think about how to quantify aspects of their growth and the underlying causes of their diverse forms. Yet, as much as I immerse myself in the downstream technicalities of research, I find myself returning to the memory of experiencing these plants in the field — remembering the lived experience of watching hummingbirds visit Tropaeolum tricolor, of watching Tropaeolum azureum climb delicately in and among clumped native bamboos, the leaf petioles gripping the tiers of overlapping leaf blades.

One feature that stands out is the nectar spur at the back of each flower. In my time in the field, I found that the short, squat spurs of Tropaeolum azureum remind me of ducktails, while the long-spurred Tropaeolum tricolor resembles red minnows swimming in midair, the red spurs as long fishtails.

What we see when we look at flowers is subjective, and we might each have a different interpretation, even from moment to moment. We can look to the local common names for species to reveal some of the directions the human imagination has gone wi is often demonstrated in. In Chile, the native Tropaeolum species have many common names. T. tricolor is often known as soldaditos rojos (little red soldiers) and T. azureum as pajaritos azul (little blue birds). These common names, the little soldiers and little blue birds, exemplify the powerful human tendency to think in metaphors and relationships — we are prone both to anthropomorphism and to make visual connections across vast species boundaries. The flowers that I had imagined as red minnows swimming across the sky — with the name soldaditos rojos, the minnows swiftly transform into tiny soldiers standing alert in formation, with their flowers facing in one direction, staring level with the horizon, petals tucked in neatly within the bounds of the sepals. Meanwhile, the pajaritos azul have large bluish-purple petals, the fluttering wings of birds in flight.

But why do these flowers look the way they do — how are they able to achieve such variety in form and ecological function, as closely related as these species are? I’ve often found myself asking the flowers directly: How do you grow your nectar spur, your floral cup? What makes the soldaditos rojos so different from the pajaritos azul? These seemingly simple questions have driven much of my work.

Thankfully, I’m not the only botanist to admit to asking questions of the plants I study. I recall reading that the late botanist Donald Kaplan’s response to students asking him questions was frequently: “Ask the plant.” This is a mindset that anchors us to the plants we study and encourages observation of and dialogue with the plant itself, and not a textbook, research article, or professor’s interpretation. And of course, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe— the illustrious poet and playwright who is sometimes called the “father of plant morphology” (although this is a contested moniker)— was known for his multi-faceted, “all-encompassing” approach to working with plants. In Sattler’s Philosophy of Plant Morphology (2018), he makes a case for how Goethe’s work in the botanical sciences, from “The Metamorphosis of Plants” and beyond, while known for his phenomenological approach, is also influenced by his animistic and mystical worldviews.

What are our worldviews? Scientists have our own interpretive lenses when we look at our study systems– the organisms or ecosystems and beyond– on which our work hinges. Some of these lenses are ones we consciously adopt over time, as the framework for our research. Others are more unconscious, as I’ll explore later.

In my research, I have looked at flowers through the lens of comparative morphology—the study of the diversity of flower shapes. In doing so, I think about the underlying anatomy of the flowers, as well as aspects of their evolution and development. I try to synthesize information from multiple disciplines: genetics, morphology, systematics, ecology, and development. I am searching for large-scale patterns and threads that connect into a single, integrated interpretation.

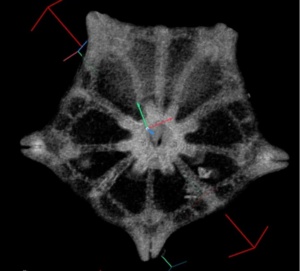

I combine the lens of comparative morphology with methods such as CT scanning that bring the ability to see into the developing flowers of the soldaditos rojos and pajaritos azul, starting when they are just a small cluster of cells, up until their petals open. You might be surprised by the idea of CT scans of flowers. You might have even gotten a CT scan of your own body, and know that it is hard things like bones that appear on the scan. The delicate ephemerality of flowers seems especially unsuited to such techniques. There is preparatory work involved— fixing the flowers in the field with FAA, a formaldehyde-based solution. Soaking them in phosphotungstanate to make the tissues more electron-dense.

As I scan multiple flowers along the same plant stem, I observe how their floral organs arise in distinct whorls, from outer to inner layers. The scans reveal the internal anatomy in incredible detail, revealing tissues composed of patterns of individual cells, depending on the resolution of the scan.

On the CT scans, the denser parts of the flowers appear white or light gray, while lower-density areas show up as dark gray or black. The vascular tissue is some of the higher density parts of the flowers. The vascular tissue appears on the CT scans as small streaks of dense cloudiness that, through the course of the development of the flower, expand and form intricate root-like branching patterns. It’s almost like discovering a hidden root system within the flowers themselves. What role does the vascular tissue play for the flower? Flowers need a lot of resources: first the vasculature transports the resources the flowers need to develop and elaborate their whorled organs, then continues to supply the water needed for the tissues to remain turgid in the bright Chilean springtime sunshine, and the sugary resources for the nectar within the spur, as a reward for visiting pollinators.

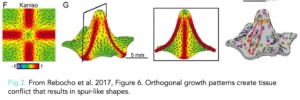

We can also see on the CT scans what it looks like when the nectar spur is just starting to form in the flower. We can see a denser area on the scan, a localized region of a mass of dividing cells. They look out of place on the scan— a hazy island of frenetically dividing cells surrounding three out of the 10 perianth vascular bundles only. What is happening here? One of the driving forces behind floral shapes is tissue conflict—a phenomenon where the cells grow in different directions and rates, creating conflict in the form of mechanical forces (see Bull–Hereñu et al., 2022 for more on this). The hazy region on the scan are cells that are not only rapidly dividing, but doing so at right angles against each other, creating conflict, a mechanical pressure that eventually warps the tissue. In the case of the flowers of Tropaeolum, the mass of dense dividing cells creates so much pressure that it drives the spur’s growth and reshapes the flower. So, we can see how tissue conflict can spur growth in unexpected ways, like the formation of nectar spurs.

Reflecting on this concept of conflict or tension leading to growth in new dimensions, I have been inspired to think beyond the bounds of flower development and will venture off here into the realm of the personal. Tension, whether in the form of cellular conflict or life challenges, can sometimes lead to new forms of growth. This is the first lesson from my own fledgling list of “Lessons from Flowers”, inspired by Beronda L. Montgomery’s Lessons from Plants, a book we discussed in lab meetings a few years ago.

The connection between tension and the opportunity for new growth also parallels my own personal journey. In 2022, I was a UFBI graduate fellow preparing to graduate the following spring, but I had to take time away from UF and my research due to health issues. I wasn’t able to come back until fall 2024, spending almost two years away from my work. During this challenging time, I was fortunate to receive the support and flexibility of Pam, Hampton, and Flora at UFBI, and many others at the university, as well as beyond, from my partner, family, and friends. This was a time in my life with a lot of grief and uncertainty. The tension I experienced between my health and academic goals was overwhelming, and these oppositional forces felt, for a time, impossible to reconcile. Yet, just as tissue conflict shapes nectar spurs, this period of personal struggle eventually led to growth in a wholly new direction—a kind of spur, if you will.

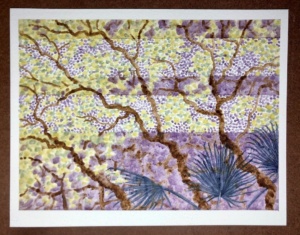

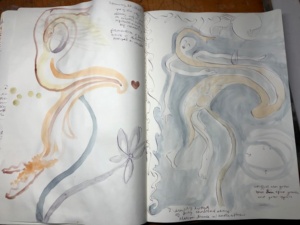

During my time away, I spent most of my time sleeping, doing self-care, and visiting doctors and other health practitioners. My academic career came to a standstill; our home and previously well-tended garden fell into disrepair. Continuing with a burgeoning interest in using plants as sources of colorful dyes and pigments, I started making art materials from the plants, fungi, and lichens found around my home. Using coffee filters, hot water, and basic chemistry, I began to extract pigments from various sources— reddish-browns from the bark of cherry laurels (Prunus caroliniana); rusty orange from the tubers of greenbrier (Smilax); vibrant yellows that fluoresce under UV light from the flowers of fumewort (Corydalis halei); rich purples from the wind fallen, spreading sheets of palm ruffle lichen (Parmotrema tinctorum)— and turn them into watercolors and inks that I began to create with. I also began playing with a process called botanical contact printing (also known as eco-printing), using heat and pressure to coerce plant pigments onto mordanted paper or fabric.

I credit the process of making art with plants, lichen, and fungi as a huge part of my recovery mentally, emotionally, physically, and spiritually. There was grief, frustration, and disappointment for me involved in stepping away from my work right when I wanted to lean in and finish projects I had been working on for years during my Ph.D., and fear that I would ever be able to return and finish. Would my Ph.D. always remain 90% complete, various manuscripts forever unseen? Would I ever feel better? I experienced that leaning into my creative practice made me more resilient— it was a bright spot, a source of flow and joy. Additionally, creating art materials and artwork from the plants, lichens, and fungi from around my home reminded me of ways of seeing and connecting with nature from a different lens than that of scientific research.

As I have started to connect with other artists online who create using pigments from plants, I am struck by how many of them use the same word that has bubbled repeatedly to the forefront of my own mind: alchemy. There is something about participating in the transmutation of plant to paint to artwork that feels it warrants this connection to the eccentric, multi-faceted ancestor of modern science. Alchemy is a word that evokes of spiritual and psychological depth (helped by Carl Jung’s alchemical studies), visual richness transcendence and mystery, conjured to the present from the mistiness of the 17th century.

Scientists can also be artists and poets and dancers and singers and developing the cognitive flexibility to shift between different ways of being will likely make us better scientists, communicators, and humans in the long run. The art I made initially— while a celebration of botanical shapes and colors, beauty and emotions— had nothing to do with my research. I still shared some of it above because I believe strongly in the value of art for art’s sake, without the end goal of science communication.

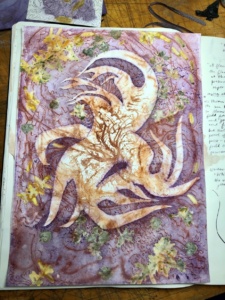

Since I have returned to my botanical work, I have also kept up a creative practice, and an invigorating bridge has begun to form between my art and dissertation research. One way that this bridge takes shape is the rhythm between my dissertation work One of the ways I’ve reconnected with my dissertation work after such a long hiatus has been through journaling and art with my plant/lichen/fungi inks and watercolors. When I have a lot of writing and analysis to do, I find that alternating between linear thinking—needed for the rigorous work of research—and the more playful, broader thinking I employ while making art or journaling. Letting the wonder re-emerge.

Alternating between the linear and nonlinear also helps me see patterns and processes in a new light. I began to think about the multitude of ways to see and interact with the plants I study, and think of ways of incorporating plant-based art materials into outreach projects. I also began to envision and plan artworks uniting seeming opposites, like the high-tech methods used to create CT scans, and the ancient techniques of creating paints from local plant, lichen, and fungi.

Leaning into art and creativity in my own work has helped me maintain my health and navigate the challenges of research and life— my creative practice is the spur that developed out of tension and conflict. By embracing both art and science, I’m able to continually draw inspiration from the flowers themselves, allowing their forms and growth processes to inform and enrich my work.

I also want to acknowledge that I was given support that few people have access to, of the millions upon millions worldwide of those suffering with long-COVID and other chronic health challenges and/or disabilities. Pausing for the length of time that I did was once inconceivable to me. Culturally, we do not have a robust framework for such extended periods of rest, and (unfortunately) needing even meager support can come with feelings of shame and failure. It was truly only possible for me because I received enormous amounts of emotional and financial support from my partner, family, and friends. I saw an excellent therapist who wisely encouraged me to prioritize making art and helped me reframe my struggles. I began to learn Pilates and Tai Chi as new ways of taking care of myself and found excellent local instructors and supportive communities. I received all this help and far more, and I am deeply appreciative— and I recognize that I am very much the exception.

Thinking of the countless who have not had the same privileges, I think it is important to be transparent about my support. I didn’t do it alone or pull myself up by my bootstraps. Chronic health conditions and disabilities impose hard limits on the extent that a person can ever attain the expected productivity of a “normal life.” To the extent that healing is possible, it almost always takes longer and costs more than is convenient, or even feasible, in our busy, individualized lives. While many people— due to their individual circumstances and by virtue of sheer determination— find ways to push through and keep working or taking care of their families, they often cause long-term damage to their health in the process. There are always hidden costs. Many others simply cannot bounce back and are pushed under by successive waves of illness, burnout, and failure into homelessness, destitution, and deaths of despair in the worst cases, or simply into lives that were much smaller than they had wanted for themselves.

So, all of these things that I have written about— flowers, rest, creativity, self-reflection, and connecting to nature all sound like luxuries in normal academic life, with lab work and analyses to be completed, and manuscripts, conference abstracts, and grant proposals to be written. What role can such insignificant pursuits— meandering stroll with the flowers, or a paintbrush dripping with an orange paint made from a Smilax tuber taken from my neighbor’s front lawn— play in the midst of global turmoil?

Let’s be honest about what is lost when we do not make time for flowers and art— or whatever your equivalent is. Flower is the nexus, a connective point between pollinators, environment, evolution, developmental processes, genes, other plants, society, art, spirituality, history, psychology— the site of a kind of spiritual anastamosis, in Goethe’s words. What connects you to everything else? The flower is both the focal point and the entire web of connection between all the various. For me, meandering with flowers meant working to maintain a relationship with the flowers beyond my subject. This meant reading in the humanities. As Francis Halle pointed out, botanists should really look to the poets to understand our subjects. The French poet Francis Ponge wrote the following, almost precisely a century ago:

“The flower is one of the typical passions of the human spirit. One of the wheels of its merry-go-round. One of its routine metaphors.

One of the involutions, the characteristic obsessions of this spirit.

*

To liberate ourselves, let us liberate the flower.”

-Francis Ponge, excerpt from “Frenzy of the Details, Calm of the Ensemble” (1926), translated by Jonathan Larson

Let’s listen to Francis Ponge and consider liberating the flower, and ourselves, from the confines of purely mechanistic thinking. Let’s remain open to other worldviews.

Art, meanwhile, can be whatever allows you to become receptive to something beyond your immediate moment. Key attributes to help you know if you have found your version of art: flow state, expressive and regenerating energy, timelessness.

For me, both these broader understandings of the flower and art develop and open “the eye of the eye”, as ee cummings put it.

I recognize that not everyone has the same need for creativity that I do or is as thoroughly entranced by flowers. But we must have something that restores our voices. I loved the books Francis Halle’s In Praise of Plants and Robin Wall Kimmerer’s Braiding Sweetgrass, and Francis Ponge’s phenomenological vegetal poetry.

Art was threaded throughout my dissertation far before I became ill, but it was never something I found possible to prioritize with any consistency, sometimes with years between creative projects. Because I did not make time for flowers (in the broadest sense of the nexus) and art, over the course of graduate school, I lost the muscle tone in my hands that allowed me to draw with precision, my regenerating connection with plants, and feel that I slowly lost my voice. How much did these losses, invisible and seemingly insignificant from the outside, contribute to my chronic pain and fatigue? Loss of voice led to lack of ability to communicate with mentors and collaborators, myself.

However, I am certainly not the only one speaking out about the necessity of the arts and humanities in the sciences. I almost publicly whooped out loud in happiness when I heard Sandy Knapp’s answer to Bharti, one of my lab members, inquiring about which fields might be overlooked in terms of science needing to collaborate with? “Arts and humanities, without a doubt,” said Dr Knapp. I have been chomping at the bit to apply to the summer program for graduate students Dumbarton Oaks program in Plant Humanities since I first saw it but still tending to health and finishing my dissertation— an out-of-state month-long commitment doesn’t work for me yet. I’m hoping that others in the plant sciences take that approach. Also, Kirk Johnson and Ray Troll, two talks from them in two days. encouraged me to write.

We must find ways to imagine a different future, remembering to be playful. I’m thinking of ways to heal divisions, cross ideological boundaries, and connect siloed fields. Connection to each other and nature— seeing the world as alive, worthy of our admiration, respect, and care. Creativity helps grow the spur of the self, stretches us into new dimensions, replenishes us with nectar. Remembering the view of the vascular system of the flower as a root system on the CT scan— every flower needs adequate resources to form in the first place, and in order to produce nectar, or set fruit and seed. We are no different.

What can we do— how can we reshape ourselves as scientists so that the public receives more of the nectar of our work? What are the needs of people? Humans want to anthropomorphize plants, be held in thrall by their beauty, enter into relationship with plants. What can we do as scientists to be more evolvable.

Practical vs. impractical. Flowers remind us that ornamentation matters, beauty matters, pattern matters. Even something brief, ephemeral can have lasting impact. Presence, pattern. The way that we make ourselves available to the contours of floral visitors, with their own needs and preferences— matters.

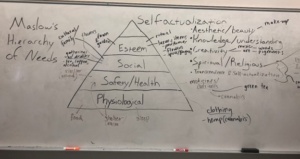

Closely related plant species that flower in the same place and time develop their own niches Flowers take on vastly different forms in order to differentiate themselves from one another and fill specific relationships. As scientists— lean into the diversity of our shapes, consider the potential of what we can offer the public with our work. Humans have a relationship with plants that runs much deeper than facts and industry. Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs.

Opportunity to be clear about what is really important. In a moment of tension, sit with the discomfort, and see if a playful connection with nature, a moment of joy with flowers, can bring a shift, evoke a spur. Assuming the best of each other.

Many biologists I have met have had a moment of connection, reverence for their study systems, fascination with the patterns and processes of life itself. Hold onto wonder, and find ways to turn it into nectar, for oneself and others.

For several semesters, I had the opportunity to TA the class “Plants in Human Affairs”, essentially an Economic Botany class. After hearing the professor of the class, Dr. Norman Douglas, lament at how narrow the range of plants were that students selected for their semester “Plant Expert” projects, I tried out a group brainstorming and discussion activity with students during the lab class using Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. I really enjoyed listening to the student’s suggestions and explanations. I also encouraged them, that when choosing a plant for their Plant Expert projects, to think if there is a particular area of their lives, of their own needs, that they were really interested in exploring through their chosen plant semester projects . One of the students told me later that he had chosen to work with a species of tropical hardwood because he was interested in connecting with his love of playing music more, and he learned his guitar was made of that wood.

This brings me back to the value of celebrating such messy and seemingly unscientific things as subjectivity, metaphors, emotions, beauty, anthropomorphization, and personal connection as a botanical researcher. These are all valuable aspects of our humanity, bringing meaning-making and connection, and have the power to transcend the strict facts of the work and weave new connections and ways of seeing. We can find deeper significance through the sweet nectars of playful imagination and connect with the life forms at the center of our research in ways that are both scientific and deeply personal.

What lessons do plants have for us during this time? How can scientists lean into creativity? How do the shapes and developmental trajectories of flowers impact us beyond an understanding of basic science? Humans and pollinators alike are drawn in by the ornamentation of flowers. The patterns of flowers are deeply resonant for a reason. Whorls of delicate symmetry; pattern with nectar at the center. Humans need beauty- beauty signifies intentionality, presence. Why be present, in a world without flowers?

** I came home inspired from the art/science event at the museum on Thursday with Kirk Johnson and Ray Troll and sketched out in my journal (with my botanical and lichen inks and watercolors) an idea for a nectar spur art piece linked to this writing— an anthropomorphized spur of the self.

Literature Cited:

Bull-Hereñu, K., Dos Santos, P., Toni, J. F. G., El Ottra, J. H. L., Thaowetsuwan, P., Jeiter, J., Ronse De Craene, L. P., & Iwamoto, A. (2022). Mechanical Forces in Floral Development. Plants (Basel, Switzerland), 11(5), 661. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants11050661

Montgomery, B. L. (2021). Lessons from plants. Harvard University Press.

Sattler, R. (2018). Philosophy of plant morphology. Elemente der Naturwissenschaft, 108, 55-79.

Palash Sethi

The Invisible Architects: BioLLMs and the Microbial Blueprint of Life

The Essential Microbial World

“Life would not long remain possible in the absence of microbes.”—Louis Pasteur

Or would it? Humans might survive without microbes, but only for a few days. And if we count mitochondria and chloroplasts as bacteria, as we should, the impact would be immediate. Most of us would be dead within minutes, and ecosystems would collapse soon after1. Microbes don’t just support life; they are the scaffolding that holds it together.

What exactly are these microbes? They are microscopic organisms such as bacteria, viruses, and fungi that are found throughout various environments, including soil, water, air, and even the human body. While some can be harmful, most exist in balance with their surroundings, playing essential roles in nutrient cycling, ecosystem stability, and biodiversity. In nature, these microbes don’t exist in isolation; they form complex, interconnected communities known as microbiomes. Functioning as dynamic ecosystems, microbiomes shape nutrient cycles, ecological balance, and, in the human body, influence digestion, immunity, and overall health2,3.

The Microbiome Crisis

Yet despite their fundamental importance to all living systems, these essential microscopic worlds face a potential crisis. Like the rainforests and coral reefs we can see, microbiomes can go through their own biodiversity collapse, with consequences just as dire. Dysbiosis—the disruption and impoverishment of microbial communities has been identified as a significant factor contributing to the chronic disease epidemic4. This connection between microbial diversity and human health is why modeling the microbiome is not just scientifically interesting, but medically imperative.

Modeling the microbiome is crucial as it helps quantify diversity, assess stability, and predict functional shifts within microbial communities. By identifying keystone species and understanding microbial interactions, these models could provide insights into how biodiversity loss alters microbiome function and resilience.

Modeling from First Principles

Let’s approach microbiome modeling from first principles by defining what an ideal model would look like in a perfect world. Why focus on an ideal scenario? Because reality presents significant challenges in accurately identifying microbial species within a microbiome, particularly without whole genome sequencing (WGS).

Traditional microbiome analysis relies on operational taxonomic units (OTUs) rather than species identification. These OTUs are created by clustering DNA sequences with approximately 97% similarity, typically using 16S rRNA genes. This approach exists out of necessity: microbial species boundaries remain poorly defined, many microbes resist laboratory cultivation, reference databases remain incomplete, and 16S rRNA sequencing lacks the resolution for reliable species-level identification. However, OTUs come with substantial limitations as they provide relatively low resolution and cannot reliably distinguish closely related microbes. WGS offers a solution by enabling identification at the species or even strain level. For our ideal model, therefore, we’ll assume access to either strain-level data from natural microbiomes or, alternatively, synthetic microbial communities. These synthetic communities can be methodically assembled from the bottom-up in controlled environments using species with fully characterized genetics and precisely known initial abundances5.

From Genomes to Features

So what defines a microbiome? At its core, it’s about the species present and their abundances. Our ideal model needs to capture the relevant features based on our specific goal: understanding how biodiversity affects microbiome traits. To do this effectively, we need features that functionally characterize each species while accounting for their abundance in the community. Think about it, microbes are typically distinguished by their phenotypes (or traits). For example, Bergey’s Manual of Systematic Bacteriology, classifies bacteria based on structural and functional attributes6. These phenotypes are likely driving forces in how microbial communities form and function.

What if we could transform species genetic sequences into meaningful phenotypic features? That would be ideal! Recent research shows that we can predict metabolic functions of both individual species and entire communities from genetic information7. Tools like Traitar already classify genome sequences into phenotypes8.

But here’s the challenge: we don’t know in advance which species phenotypes we need to effectively map from species characteristics to microbiome behavior. So instead, we need a transformation that converts genetic sequences directly into useful genetic features, a representation that captures the functional essence of each microbe in our community.

The BioLLM Revolution

And this is where recent Bio-AI models—specifically BioLLMs—change everything! While you might think of AI models like ChatGPT or Claude as text generators, BioLLMs have a completely different generative superpower: they create embeddings from genomic sequences. What are embeddings? Think of them as dense numerical representations that capture the essential properties of biological sequences. They encode evolutionary relationships, structural patterns, and functional information in a way that makes biological data far more meaningful to AI systems than raw sequences could ever be.

The impact of these models has been remarkable. Take ESM9, which can predict protein functions like enzymatic activity and structural stability with surprising accuracy. BioLLMs are revolutionizing genomic annotation too, by identifying novel genes, classifying protein families, and detecting antimicrobial resistance markers. Perhaps most fascinating is how these models capture evolutionary relationships. The embeddings naturally contain phylogenetic signals that dramatically improve species classification and comparative genomics. Some researchers are even using BioLLMs to generate entirely new proteins with specific functional properties, opening exciting frontiers in synthetic biology and drug design10.

By harnessing these models, we’re moving far beyond traditional sequence analysis into a realm where hidden biological insights become visible. As our ability to extract meaningful representations from genomes improves, so does our capacity to functionally characterize microbes, predict ecological interactions, and truly understand microbiome biodiversity.

The Evolution of Modeling Approaches

Now that we have taken care of the data, and its pre-processing to generate embeddings, let’s think about the model capabilities. Early microbiome modeling relied on linear statistical approaches like ordination methods (PCA, PCoA) and regression models11, which helped identify correlations between microbial composition and environmental factors. These models provided a basic understanding of microbial diversity but struggled to capture complex, nonlinear interactions. To address this, nonlinear models such as network-based approaches and dynamical systems models emerged. These included co-occurrence networks that inferred microbial interactions and Lotka-Volterra models, which described microbial population dynamics over time12,13. While these models improved interaction mapping, they still required strong assumptions and were limited by noise in microbiome data.

With the rise of high-throughput sequencing, machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) models have transformed microbiome analysis. ML models like random forests and support vector machines have been widely used for classification, biomarker discovery, and disease prediction. More recently, deep learning, including neural networks, graph-based models, and transformer-based BioLLMs, has been leveraged for microbiome function prediction, metagenomic annotation, and drug-microbiome interactions14. These models capture complex, high-dimensional patterns without relying on predefined assumptions, making them powerful tools for microbiome research.

The Future of Microbial Understanding

As we stand at this inflection point between traditional microbiome analysis and AI-powered modeling, we glimpse a future where microbiome science transcends its current limitations. By combining genomic embeddings from BioLLMs with advanced modeling architectures, we’re not just incrementally improving our understanding. We are fundamentally transforming how we perceive microbial communities. These new approaches promise to bridge the gap between sequence data and functional insights, revealing the hidden mechanisms through which microbiomes shape our world. Just as Pasteur recognized that life depends on microbes, we now recognize that understanding life depends on modeling these complex communities with tools equal to their sophistication. In protecting and harnessing the power of our microbial scaffolding, we may find solutions to some of our most pressing challenges, from chronic disease to environmental degradation, all hidden within the invisible world that makes our visible one possible.

Viviana Rojas Bonzi

Exploring the Chaco: From Biodiversity to Battlefields

For many of us working in conservation, going out into the field for sampling campaigns is an exciting, exhausting, but necessary adventure. It’s not just about collecting data; it’s about satisfying that spirit of freedom we carry within us. Without a doubt, the field of conservation involves a wide variety of sampling types. Some require early mornings to catch the first bird songs, while others, like my work, involve setting up monitoring equipment and later evaluating the presence of certain species through captured photographs. Then there are colleagues who must sample by moonlight, such as those studying amphibians or bats. In all cases, field campaigns are filled with unforgettable experiences and lessons of all kinds.

For me, one of the greatest lessons during these years of fieldwork has been (and continues to be) learning more about the cultural and historical value of the places where I work. Specifically, I’ve been learning about the historical events that have marked the ground where I now walk, sampling to conserve endangered species. Often, we are so focused on the biological importance of our sites that we overlook the other relics they hold. Working in the Chaco of Paraguay has allowed me to delve deeper into the details of one of the most recent and painful historical events in my country’s history—the Chaco War.

The Chaco War was fought between Paraguay and Bolivia from 1932 to 1935 over control of the Gran Chaco region, which was believed to be rich in oil. It is estimated to be one of the bloodiest conflicts in Latin American history, with estimates of around 100,000 deaths of soldiers from both countries. History narrates that Bolivia was believed to have a larger and better-equipped army; however, Paraguayan forces were more experienced in the harsh Chaco environment, giving them strategic advantage. At the end, Paraguay gained control over most of the disputed territory, and the Treaty of Peace was signed in 1938, formally ending the conflict.

The Chaco War holds a deeply sentimental place in the hearts of Paraguayans. It feels like a recent memory, especially since many former soldiers were still alive until just a few years ago. I remember that during my high school years, we would visit veterans on June 12th, which is Memorial Day for the Chaco War in Paraguay. These visits were a poignant reminder of the sacrifices made and the stories that shaped our nation, and so they are referred to as the “Defensores del Chaco” (Defenders of the Chaco). The Chaco War is also very special to my family. My great-grandfather was a veteran, and although I would have loved to hear about his experiences in the Chaco, he never spoke about the war. His silence spoke volumes, leaving us to imagine the hardships and bravery that marked those years.

Over the years, I’ve had the privilege of visiting various sites in the Chaco, places that once echoed with the sounds of battle. You can still see the trenches where soldiers sought refuge. Also, many private reserves have dedicated a small space to create local museums where people have gathered artifacts from the war—cartridges, bottles, and more- found around.

When traveling to secluded corners of the Chaco, you might be surprised to find a relic of the war, like an old cemetery. These forgotten graves often bear no names, just a year crudely etched—perhaps with a knife—into a wooden cross, with a helmet resting on top. Occasionally, you might even spot the mark of a bullet on the helmet. These anonymous soldiers rest in a land that might not have been their birth land, as during the war, men from various parts of Paraguay were recruited to fight, many of whom had never set foot in the Chaco before.

To this day, there has not been a single field campaign where I don’t get goosebumps thinking about the harsh conditions soldiers endured during the war. The pressing heat, the harsh vegetation, the dangers of being unprotected from insects and mosquitoes, or from venomous snakes such as rattlesnakes (“mboi chini”, in Guarani) or pit vipers (“jararas”, in Guarani). The Chaco is a land steeped in history, where the echoes of battles still whisper through the trees. During the day, the sun illuminates the scars left by war, each mark telling a tale of bravery and hardship. As night falls, the shadows seem to come alive, replaying the events of those tumultuous times. It’s as if the land itself remembers and retells the stories of those who fought and lived through those days, ensuring that what they went through is never forgotten.

Sign at Eugenio A Garay locality. It reads “Welcome to Gral Eugenio A Garay, where the weak becomes strong, the coward becomes brave and tears are merely sweat drops”. Photo: Viviana Rojas.

One of the most frequently told tales in the Chaco is that of a mysterious light appearing in the middle of the road at night. I had my own encounter with this phenomenon during my last field season. The roads in the Chaco are dirt paths, surrounded by dense vegetation, and illuminated only by the stars and the moon. Every light stands out starkly against the darkness, making it impossible to miss.

One evening, we finished our sampling much later than planned and began our journey back to camp. Although it was only around 8 PM, the winter sky had already swallowed all traces of daylight. We were exhausted, and it took us a few minutes to realize that we had been seeing a light in the distance for quite some time without ever reaching it. We all started paying closer attention, expecting another vehicle to pass by us at any moment.

Minutes passed, and the light remained elusive. Finally, one of us broke the silence, saying, “I think that is the Bolivian truck, you know… from the war.” A chill ran down my spine. As it turns out, we were not the only ones to have this experience. The Bolivian truck is a common sighting at night in the Chaco. According to the legend, you’ll see the truck’s lights and hear its engine, but you will never reach it. The light will vanish as mysteriously as it appeared.

I had never experienced anything like this before, and to be honest, I was a bit skeptical. But that night, the legend of the Bolivian truck felt all too real.

After this experience, I realized that in the Chaco, the past is never truly gone. It lives on in the stories passed down through generations, in the monuments and memorials, and in the very soil itself. The Chaco is not just a place; it’s a living testament to the resilience and courage of those who came before. And as you stand there, you can’t help but feel a deep connection to the history that shaped this land and its people.

Hernan Alvarez

From Childhood Adventures to Scientific Curiosity to Understanding People: My Journey into the Human Side of Biodiversity Conservation

In this blog, I’d like to share with you some of the key moments and experiences in my life that led me to study biology and, eventually, grow my interest in understanding human behavior in biodiversity conservation. I’ll begin by recounting a few childhood adventures near my hometown, as I believe these early experiences were what first inspired my fascination with nature. I was born and raised in a small city in the Ecuadorian Andes called Latacunga. One of the most magical things about this town is its location in the foothills of one of the world’s highest active volcano—Cotopaxi, which rises to an elevation of 19,347 feet (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Cotopaxi Volcano, located in the central Andes of Ecuador (Source: https://www.wired.com/2015/08/cotopaxi-ecuador-erupts-first-time-since-1940s/)

The Cotopaxi Volcano is located within the Cotopaxi National Park, a protected area that preserves the natural landscapes of the highlands and the ecosystems surrounding the volcano. Growing up near this park gave me the chance to connect with nature from an early age. My passion for the outdoors really began during family camping and fishing trips to the highlands of Ecuador. I spent those adventures with my father, uncles, and cousins—we were definitely an outdoor family back then. Those memories of sleeping under the stars, hiking through páramo grasslands, and waking up to the sight of snow-capped peaks shaped my appreciation for the natural world. They taught me to enjoy being in nature and to value the stunning landscapes of the Ecuadorian Andes.

One of the most influential people in my life was my uncle, who earned his Ph.D. in Conservation Biology at the University of Minnesota. He played a major role in shaping how I saw the natural world—not just as a place for fun and adventure, but as a living, breathing classroom. Thanks to him, me and my cousins began to see nature through an ecological lens.

During our trips to the highlands, we spent time observing wildlife—especially birds like the Carunculated caracara and the American Kestrel (Falco sparverius)—and exploring the diversity of highland plants. We’d listen closely to the sounds of birds and the wind sweeping across the mountains. But part of the thrill was that nature could also be unpredictable.

One of my most vivid memories is an unexpected encounter with a herd of bulls during a fishing trip. A few of us had our fishing lines in the water, while others lay in the grass, enjoying the sounds of birds and the wind across the mountains. Suddenly, someone shouted, “Bulls!” In a moment of panic, we all jumped into the stream to get out of the way. As it turned out, the herd veered off in another direction—but what began as pure fear quickly became one of our most legendary family stories. These adventures laid the foundation for my deep love of the outdoors. They taught me to appreciate wildlife, to observe the natural world with curiosity, and to find joy in being surrounded by it. Encouraged by my uncle’s example, I came to understand that nature could be both a place of wonder and a subject of serious study—eventually leading me to pursue a degree in biology.

Between 2007 and 2010, while pursuing my bachelor’s degree in biology at Universidad San Francisco de Quito, I had the chance to participate in a variety of projects—from researching primates in the Ecuadorian Amazon to helping eradicate feral cats on La Isla de Plata, a small island off Ecuador’s Pacific coast. Toward the end of my degree, in the summer of 2009, I completed an internship at the Center for Tropical Research (CTR) at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA). There, I worked on evolutionary studies of tropical birds—research that would later form the foundation of my undergraduate thesis. These experiences introduced me to the excitement and significance of scientific discovery and biodiversity conservation. Yet, as my career progressed, I began to realize that protecting biodiversity isn’t just about studying species and ecosystems—it also requires a deeper understanding of how human actions shape the natural world.

In 2010, shortly after graduating, I began working in Yasuní National Park and the Yasuní Biosphere Reserve (YBR), located in the western Amazon of Ecuador (Fig. 2). I was involved in conservation projects focused on environmental education in Indigenous communities, aiming to raise awareness about waste management and reduce pollution—especially from plastic. In a second project, I helped train local community members as wildlife monitors, supporting them in collecting and analyzing data on medium- and large-sized game mammals and bird species.

Through these experiences, I witnessed firsthand how deeply human knowledge, values, culture, and decision-making are intertwined with conservation outcomes. Encouraging communities to adopt new practices was far more complex than I had anticipated. It became clear that lasting impact couldn’t come from individual behavior change alone, community decision-making processes and collective norms also played a crucial role. This added a new layer of complexity and made me realize that conservation is as much about people as it is about ecosystems.

On top of that, I developed a strong connection with the local people, when I realized that they also were interested in learning ways to help protect their natural resources, defend their lands from external people and oil companies. They looked at us (the people implementing the project), as persons that can truly provide them technical knowledge to help their communities to improve their decisions to manage their natural resources. This to me was one of the most important realizations I had at this point in my career. Especially because, at school, as I studied conservation biology, I was always taught that human actions create an impact on biodiversity, which is true, but no courses or professors told me that local people living near these regions are often the most committed to finding sustainable solutions. At this point in my career, my conclusion was that we need to understand how the involvement of local people in conservation initiatives—not only biologists or ecologists—can improve conservation outcomes.

To deepen my understanding, I pursued a master’s degree in Wildlife Ecology and Conservation at the University of Florida, with a specialization in Human Dimensions and Tropical Conservation and Development. My research focused on identifying the factors that influence the success of community-based conservation initiatives in the Ecuadorian Amazon. This work gave me the opportunity to interview various stakeholders—especially local community members—about their involvement in different stages of conservation planning and implementation. One of the key findings was that participation at every stage from design through implementation was associated with both conservation success and community empowerment.

After completing my M.Sc. in 2015, I returned to Ecuador to work for a Conservation International NGO, Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS). During my time there, I was involved in a wide range of conservation projects and collaborated with diverse local actors, including Indigenous communities, government agencies at both the local and national levels, other NGOs, and private institutions. This experience significantly expanded my understanding of what effective conservation requires and deepened my appreciation for the complex interplay between ecological and social systems. My work involved developing wildlife management plans and action strategies to address the impacts of commercial and illegal hunting in the Yasuní Biosphere Reserve (Fig. 3). I also collaborated with partners to strengthen the governance capacities of Indigenous organizations and public authorities, and I contributed to research on human–wildlife conflict—particularly local perceptions of jaguar conservation. These experiences reinforced my belief that real progress in conservation depends on understanding the full spectrum of factors that influence human behavior, both at the individual and collective level.

Figure 3. Participatory workshop with community members to develop a community-based natural resources management plan (Credits: Ruben Cueva)

Through my extended experience working on conservation from the human dimension’s perspective, I learned that many institutions such as governmental and non-governmental, public and private, are working hard to implement a wide range of natural resource conservation strategies. These include regulatory measures to sustainably manage or prohibit the use of protected species, economic incentives to promote sustainable practices, alternative livelihoods to reduce illegal or unsustainable extraction of wildlife, and environmental education campaigns to raise awareness about threats to biodiversity and the importance of conservation. Yet, despite all these efforts and the significant resources invested, biodiversity continues to decline, deforestation persists, and environmental pollution remains a critical issue.

Thus, as I gained more experience in the field, I began to notice a pattern, no matter how sound the science was, conservation efforts often struggled when they didn’t account for people. I started asking questions that biology alone couldn’t answer: Why do communities sometimes resist conservation initiatives, even when they benefit from biodiversity? What drives people to comply with or ignore environmental regulations? And how can conservation strategies be designed in ways that align with people’s values, livelihoods, and cultures? These questions led me to a turning point. I realized that to truly make a difference, I needed to understand not just the species we’re trying to protect, but also the human behaviors and social systems that influence conservation outcomes.

These questions led me to my current academic path, where I am now pursuing a Ph.D. in Interdisciplinary Ecology at the University of Florida’s School of Natural Resources and the Environment, with a concentration in Sociology through the Department of Sociology and Criminology & Law. In an upcoming blog post, I’ll share more about what I’m working on in my current program and explore some of the key theories I’ve learned that help explain human behavior in the context of conservation and environmental regulations. Stay tuned!

Rick Stanley

Ecosystem Recovery in the Dominican Republic

For those of us who work in environmental fields, the degradation of ecosystems around the globe can appear dire. However, damage to ecosystems is not always irreversible: given enough time and support, restoration efforts can help bring back entire habitats. In this blog post, I would like to share some personal thoughts on the topic of restoration, and to ask the question: ‘what lessons have I learned about ecosystem recovery as an ecologist conducting fieldwork in the Caribbean?’