Mountains of Miami

Mountains of Miami

By Lauren Trotta

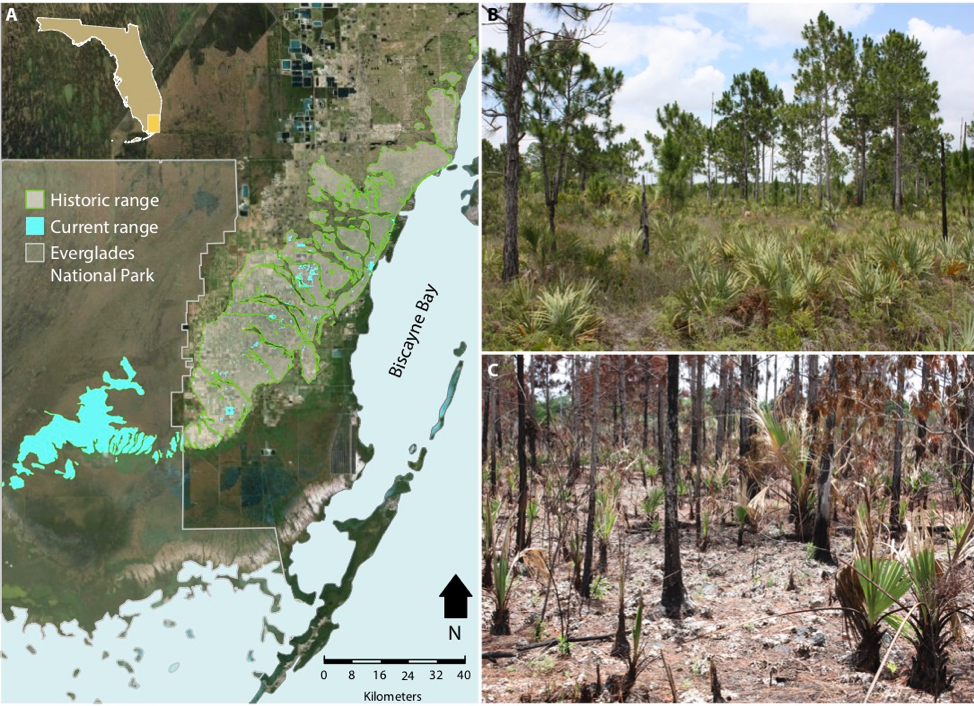

At the southernmost point of peninsular Florida lies the Miami Rock Ridge. Stretching along the shore of Biscayne Bay in Miami-Dade County and curving westward as Long Pine Key into Everglades National Park, this area is the elevational apex of the surrounding lands. Here, oolitic limestone1 bedrock is exposed to the elements, and the portions that remain untouched by anthropogenic development are sharp as glass, but as fragile as eggshells from millennia of period inundation and pounding rain.

The Miami Rock Ridge is notable for the juxtaposition it underlies. The habitats perched upon this harsh rocky terrain are some of the most diverse in Florida and the United States at large (1). Atop the highest elevations of the ridge (up to 7m above sea level) you will find a mixture of pinelands, with their characteristic open canopy of scraggly, widely spaced pines, interspersed with hardwood hammocks, dark and humid with heavily crowded canopies. The tapestry of high elevation habitats was once woven together by low elevation transverse glades that flowed from the characteristic open sawgrass plains of the Everglades eastward toward the Atlantic seaboard. Outside Everglades National Park, these glades have largely been transformed into canals, and the high-and-dry habitats have become prime real estate for urban and agricultural land development.2

Majestic Pine Rocklands

The pinelands that one took center stage on this ridge are called the pine rocklands, a globally, critically imperiled ecosystem analogous to the equally endangered long leaf pine ecosystem to its north in the southeastern coastal plain. While pine rocklands once encompassed an area of 126,500 acres today the largest tract of contiguous habitat is protected inside Everglades National Park while less than 2% of this once flourishing habitat remains outside the park (2).3 These highly fragmented and isolated urban “islands” are some of the only natural green spaces left in Miami-Dade, and while these areas are bombarded by a multitude of stressors, ecologically they are the crown jewels in the mosaic of Miami.

The tension between these biodiverse natural areas and the consistent expansion of human development is the setting for my graduate research. I first experienced the pine rocklands in August of 2014, about a week after moving to Florida from New England. My overwhelming thoughts during this first field excursion were that pine rockland fragments could be pointedly uninviting. Miami seemed impossibly hot, humid, and teeming with endless droves of mosquitoes. Caged by chain link fences, urban pine rocklands now greet their visitors with dense edges hosting all manner of wily plants, from the prickly and poisonous to vines, so prolific in their skills of entanglement, you would swear were sentient.

Inside a pine rockland fragment though, the wild, uninviting edge habitat abates. Gazing up, there is open sky punctuated by a sparse canopy of fluffy pine needles from the South Florida slash pine.4 From the level of your knee to your eye, you can find yourself in either completely open habitat or surrounded by large palms and squat shrubs with intermittent vines. Below the level of your knee, on the rocklands floor, a cornucopia of biodiversity bursts forward. Multitudes of tiny species have found a soil-filled nook or a humid cranny in the craggy, sunbaked limestone in which to flourish. In all, there are more than 400 species native to pine rocklands, from grasses that billow plumes of cotton-y seeds to scrambling vines and demure cushions of herbs that cling to their substrate (3). Seventeen of these native species are listed as threatened or endangered by the United States Fish and Wildlife Service, and – even more important – fourteen are endemic to this habitat (4, 5). Endemic species are those that have evolved in the area in which they are found. These species represent a unique branch of evolutionary history found nowhere else in the world.

The Cost of Rarity

While urban pine rockland fragments were once part of a contiguous swath of wilderness, they have been partitioned and gated into smaller parcels that have a unique set of management issues. The act of sub-dividing once connected wilderness, itself, results in a phenomenon called “edge-effects,” 5 where the edges of fragments tend to become different in both structure and diversity from the center core habitat (6). Historically, pine rockland habitat was maintained by periodic fires (about every 6-9 years,) which promoted a sparse canopy and moderate shrub cover (2). As the Miami Metropolitan area has grown and more people live in closer proximity to remaining urban habitat fragments, it has become increasingly difficult for land managers to perform prescribed burns. Without fire, shrubs and the canopy grow thicker and taller, over-shadowing the diversity of low-growing species that need baking sun and open spaces to thrive. Further, being situated within a matrix of residential and agricultural lands results in influxes of invasive species into these fragments. And, most concerningly, this combination of issues dwarf in comparison to the long-term threat of complete inundation from sea level rise.

So why preserve and manage these fragments? Because they are fantastically invaluable. Over the past few decades conservation and restoration efforts have been prioritized for large, contiguous tracts of land that are relatively wild, and can create pathways that allow species to disperse far and wide (a framework referred to as the 3 Cs: cores, corridors, and carnivores) (7). Recently, though there has been a recognition that by prioritizing the largest tracts of land we miss out on conserving unique and plentiful biodiversity only found in smaller, fragmented parcels that host narrow-range endemic species and important microhabitats (8-10). This is the case when we compare urban pine rocklands to those remaining in Everglades National Park. Pine rockland habitat varies greatly along Miami Rock Ridge with some endemic species only occurring in urban fragments. By conserving and restoring urban pine rocklands we preserve some of the last remaining places on Earth where narrow-range endemics are found in the wild.

Takeaways

As urbanization increases (11) and the impacts of climate change are felt more acutely across the world (12), the Miami Rock Ridge and the habitats, people, and conservation concerns it hosts are not unique. But, in many ways, they may be ahead of their time. While urban pine rocklands face daunting anthropogenically driven threats, each fragment is a singular and irreplaceable testament to the evolutionary past and future potential for many species. As the old adage goes, “good things come in small packages,” and when it comes to pine rocklands important biodiversity is found in small parcels tenuously floating in a sea of urban and agricultural lands in south Florida.

Follow Lauren on Twitter.

Check out more posts on our Biodiversity Blog.

FOOTNOTES

1 Learn more about the formation of Miami oolitic limestone.

2 Two of the most recent contentious pine rockland conservation issues include development Miami Wilds and Coral Reef Commons.

3 Pine rocklands habitats are also found on a few islands in the Florida Keys, the Bahamas, and on Turks and Caicos. Outside of the U.S. this habitat is referred to as a Pine Yard.

4 By examining the growth rings of this slow growing species, scientists have been able to reconstruct historical fire regimes and study how climate influenced wildfires (13, 14)

5 Edge effects are one factor in why some pine rockland fragments look so dense and uninviting to an outsider-looking in.

REFERENCES

- Snyder, J.R., Alan Herndon, and W.B. Robertson Jr. 1990. “South Florida Rockland.” In Ecosystems of Florida, edited by R. Myers and J. Ewel, 230–77. Orlando, FL: University of Central Florida Press. http://pubs.er.usgs.gov/publication/85776.

- Florida Natural Areas Inventory (2010) A guide to the natural communities of Florida. Florida Natural Areas Inventory and Florida Department of Natural Resources, Tallahassee

- Trotta, Lauren B., Benjamin Baiser, Jennifer Possley, Daijiang Li, James Lange, Sarah Martin, and Emily B. Sessa. 2018. “Community Phylogeny of the Globally Critically Imperiled Pine Rockland Ecosystem.” American Journal of Botany.

- U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service. 2020. Endangered Species Database. https://www.fws.gov/endangered/species/us-species.html.

- Jones, Ian Matthew, and Suzanne Koptur. 2017. “Dead Land Walking: The Value of Continued Conservation Efforts in South Florida’s Imperiled Pine Rocklands.” Biodiversity and Conservation 26 (14): 3241–53.

- Murcia, Carolina. 1995. “Edge Effects in Fragmented Forests: Implications for Conservation.” Trends in Ecology & Evolution 10 (2): 58–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0169-5347(00)88977-6.

- Soulé, Michael, and Reed Noss. “Rewilding and biodiversity: complementary goals for continental conservation.” Wild Earth8 (1998): 18-28.

- Wintle, Brendan A., Heini Kujala, Amy Whitehead, Alison Cameron, Sam Veloz, Aija Kukkala, Atte Moilanen, et al. 2019. “Global Synthesis of Conservation Studies Reveals the Importance of Small Habitat Patches for Biodiversity.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 116 (3): 909–14. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1813051115.

- Carroll, Carlos, and Reed F. Noss. 2020. “Rewilding in the Face of Climate Change.” Conservation Biology, June, cobi.13531. https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.13531.

- Harrison, Susan, and Reed Noss. 2017. “Endemism Hotspots Are Linked to Stable Climatic Refugia.” Annals of Botany 119 (2): 207–14. https://doi.org/10.1093/aob/mcw248.

- Liu, Xiaoping, Yinghuai Huang, Xiaocong Xu, Xuecao Li, Xia Li, Philippe Ciais, Peirong Lin, et al. 2020. “High-Spatiotemporal-Resolution Mapping of Global Urban Change from 1985 to 2015.” Nature Sustainability, May. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-020-0521-x.

- Southeast Florida Regional Compact 2015 Unified sea level rise projection for Southeast Florida Report (Fort Lauderdale, FL: SFRC) www.southeastfloridaclimatecompact.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/2015-Compact-Unified-Sea-Level-Rise-Projection.pdf

- Harley, Grant L., Henri D. Grissino-Mayer, and Sally P. Horn. 2011. “The Dendrochronology of Pinus Elliottii in the Lower Florida Keys: Chronology Development and Climate Response.” Tree-Ring Research 67 (1): 39–50. https://doi.org/10.3959/2010-3.1.

- Harley, Grant L., Henri D. Grissino-Mayer, Sally P. Horn, and Chris Bergh. 2014. “Fire Synchrony and the Influence of Pacific Climate Variability on Wildfires in the Florida Keys, United States.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 104 (1): 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/00045608.2013.843432.