UF Biodiversity Institute

By Karla Arboleda

Pam Soltis has spent her adult life studying the Earth’s living things, first from the perspective of plants and in recent years on a broader scale as she and her husband, Doug, have worked to create a “Tree of Life” that organizes and illustrates how all living things interact.

But as scientists came to understand the catastrophic impact of global climate change and the unprecedented loss of plant and animal species, she began looking for a better way of understanding and communicating this unprecedented challenge.

“The remarkable diversity of species and environments in our natural world is declining rapidly as the human population expands and landscapes are modified,” Soltis says. “Insufficient information and policies are in part due to the slow rate at which biodiversity data are gathered, and the difficulty in accessing the information once it is available.”

Pam Soltis is director of UF’s Biodiversity Institute.

So, in 2016, Soltis led establishment of the UF Biodiversity Institute, with a vision to “accelerate the discovery of, improve the understanding of, enhance the conservation of and disseminate information on the planet’s biological diversity.”

Today, nearly 100 scientists and scholars affiliated with the institute are collaborating to understand the relationship between plants and animals, climate change and the sustainability of natural and human environments.

“UFBI also gives us an opportunity to pull people from what we thought of as being isolated parts of the biological sciences together, because they really do represent a continuum,” Soltis says.

Among the institute’s initiatives are encouraging research and training around discovery of new biodiversity; using big data to describe, understand, explain and predict patterns of biodiversity; and translating knowledge on biodiversity into action – including conservation, policy, law and education. UFBI promotes interdisciplinary research through seed grants that jump-start new collaborations and research projects. Since 2017, the institute, in collaboration with the UF Informatics Institute, has awarded a total of $460,000 to researchers across campus.

For example, the institute funded a collaboration among scholars in the Tropical Conservation and Development Program, the Department of Geography and the Levin College of Law on a project to assist indigenous communities in the Amazon with biocultural policy and decision-making.

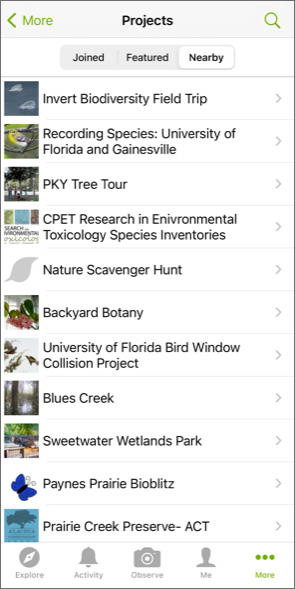

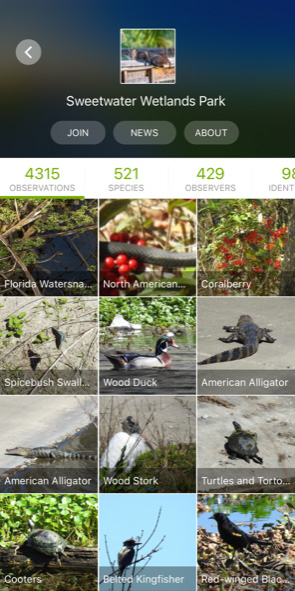

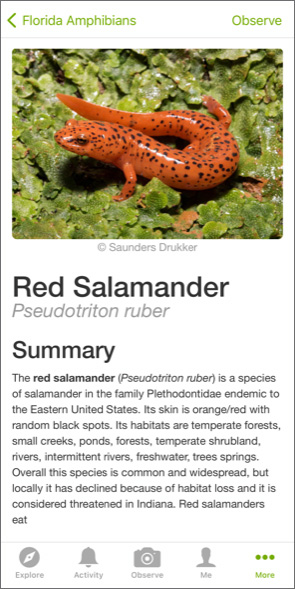

A joint grant from the Biodiversity and Informatics institutes funded a project to evaluate the quality of data submitted through iNaturalist, a platform where citizen scientists submit pictures, videos or audio of biological sightings to be identified by plant and animal experts.

“Citizen scientist contributions … with some extra quality controls can still be useful in biodiversity studies, since they cover otherwise underexplored areas, such as central Africa or Southeast Asia,” the researchers wrote in a paper in PLOS One last May. “Citizen scientist data collections have the advantage of being quickly updated, and the many eyes of volunteer contributors may even be able to discover species in locations where they were not previously observed.”

The close relationship between the Biodiversity Institute and the Informatics Institute is reaping dividends for both as the university pursues new research and recruits new faculty under the Artificial Intelligence Initiative.

With a powerful new supercomputer now online and collaborators from the Informatics Institute, Soltis says UFBI members are keen to use AI to advance their research.

“AI is opening exciting new opportunities in many areas of biodiversity science, from the use of camera traps to monitor wildlife movements to scoring thousands of plant specimens to detect changes in flowering date in response to climate change,” she says. “UF’s AI Initiative will bring new faculty to campus and will build on the strong start that UFBI scientists have already made in this field.”

Soltis and other faculty in the institute have long been involved in iDigBio, a massive UF-led National Science Foundation effort to digitize and share data for the estimated 1-2 billion specimens in the nation’s natural history museums, so they are primed to take advantage of UF’s new capabilities.

“I see digitization as a huge opportunity to help broaden participation in science,” Soltis says. “If we could deliver content to people virtually, we have a much better way of reaching people who could benefit from the types of work we do and who might want to join the field.”

Soltis says that training the next generation of scientists is another top priority for the institute, so in 2016 it began supporting 9-month fellowships that “are geared toward mid-Ph.D. students, nominated by their departments, whose dissertation projects could particularly benefit from interdisciplinary opportunities with faculty, post-docs and students outside their departments or programs.”

Among the research topics on which the five 2020-21 fellows are focusing are the impact of fragmented landscapes on carnivores in India; the fate of South Florida’s critically imperiled pine rockland ecosystem; how habitat-forming marine organisms like coral and sea urchins respond to environmental changes; the role of ants in ecosystems around the planet; and the bird ecology of fragmented cloud forests in Peru.

Soltis is a strong proponent of effective science communications, so the fellows are also required to maintain a blog about their research. During the pandemic, several of the fellows wrote about how the campus shutdown enabled them to reconnect with nature.

“About six months ago, in the midst of the pandemic, I started going for hikes around Gainesville to spend time outdoors,” wrote Mahi Puri, whose work focuses on analyzing behavioral adaptation patterns in carnivores. “Being a wildlife biologist myself and having been away from working in the field for almost a year, these hikes allowed me to be around nature again.”

Lauren Trotta, who studies South Florida ecosystems, wrote about how nighttime walks around the UF campus helped her to appreciate the different world that comes out after the sun sets.

“During these walks, the familiar verdant backdrop shifted into darkened shadows against the night sky and I began to discover an entirely new diversity of sounds, smells and creatures.”

As the UFBI completes its first five years, Soltis says, “we have facilitated new collaborations, supported interdisciplinary events, including with the arts and humanities, trained students, and more, and we’re looking for exciting new things to come during the next five years and beyond.”

This story originally appeared on UF Explore.

Source:

Pam Soltis, Director of the UF Biodiversity Institute

Related Website: